Action films are baked into the film medium's soft, celluloid tissue. Why was the movie camera invented? To watch things move. And nothing moves like a great action movie. Heck, every take starts with someone shouting, "Action!"

But what makes an action movie great? The genre is already quite subjective. Steven E. de Souza, writer of multiple films venerated below, didn't hear action identified as a distinct genre until the mid-1980s. Before then, it was scattered amongst westerns, war films, martial arts flicks, and police procedurals. Today, action films have re-diversified into superhero soaps and every other type of effect-addled blockbuster — it's hard not to find an action flick at the local multiplex. As such, for the sake of nailing down true greatness, this list includes a little of all the above.

But how does "Hard Boiled" stack up against "The Lord of the Rings"? There's apples to oranges, and then there's Jackie Chan to Arnold Schwarzengger. Seeking out the definitive, all-time, no-questions-asked greatest action film of all time is folly. As a result, the following 95 entries are listed alphabetically. Consider this a course in the essentials of running, jumping, and falling down. The only real qualification for inclusion here is that the film delivers a thrill unlike any other, whether that means Tony Jaa doing push-ups on an elephant or Rudy Ray Moore taking a night off from insult comedy to practice kung-fu. This is action, packed.

Action Jackson

The only way to torture a man like Action Jackson is to tie him up like the Steve Reeves Hercules and turn an industrial blowtorch on him. He won't break, of course, but it gives him time to come up with material. How director Craig Baxley and star Weathers handle that material is what puts Action Jackson, man and movie, in the pantheon. Cornering his captor at point-blank range with a grenade launcher, Weathers drops the punchline - "How do you like your ribs?" - like the verdict from the Hague. Instead of showing any bodily carnage, Baxley fades from one fire to another, to a half-rack smoldering on the grill.

"Action Jackson" is what other '80s action heroes go to see at the mall multiplex and clap for as the credits roll. Each scene is a new treatise on just how unbelievably cool Action Jackson is. He's sasquatch with a badge, in both legend and size. At one point he makes a perp faint just by saying, "Mellow out." The few moments that aren't dedicated to his football-sized pecs or cherry-red convertible are spent selling Craig T. Nelson as the most evil businessman martial-artist in the evil and martial artists businesses. But the channeled power of all Blaxploitation villains before him is no match for Action Jackson, the only man who drive a Pontiac up a flight of stairs by sheer force of hate.

In a just universe, there'd be three sequels and a reboot to consider for this list. Carl Weathers deserved more, but it's hard to imagine much better.

Akira

"When I saw the first rush of the movie version of 'Akira' I thought it would be a failure," creator and director Katsuhiro Otomo told Forbes. "I left the theater very quickly and came back home to tell my wife that the movie was a failure." That's faint praise for one of the most influential pieces of science fiction ever animated.

Gang leader Shōtarō Kaneda, voiced by Mitsuo Iwata, leads a violent, if uncomplicated, existence in the bilious shadows of Neo-Tokyo. He leans on jukeboxes, races rival motorcycle gangs, and hangs out with his childhood best friend, Tetsuo Shima, voiced by Nozomu Sasaki. That all changes, though, when Tetsuo totals his bike on a passing child, who takes no damage at all from the ensuing blast. Before long, the pair are knee-deep in a government cover up that involves telekinetic powers, buried remains, and hot-air-balloon body horror. But expounding on the plot of "Akira" is a waste of time and paper — there's no way to appreciate it without seeing every last one of its 160,000 cels in impossible motion.

Tendrils of smoke, sentient and searching, trail each explosion. Morse-dot traffic breaks up the neon sprawl, as seen from on high. Headlights and laser fire flash the same shade of orange as they streak by at similar speeds. The action is so singularly kinetic, that Otomo and company accidentally trademarked their own maneuver, the "Akira" slide, when Kaneda skids his motorcycle sideways. Although it's as potent a gateway drug as ever to anime, to Japanese science fiction, and to mature animation in general, nothing comes close to the super-fluid nightmare of "Akira."

Aliens

James Cameron accepted the writing jobs for "Aliens" and "Rambo: First Blood Part II" on the same day. More than any military hardware or Vietnam allegory, what connects the two projects is Cameron's singular trick for building a better sequel: When in doubt, crank up the action.

For her Xenomorph troubles, freight hauler Ellen Ripley receives PTSD and a formal inquisition over her competence behind the wheel. Now an expert only because of her pain, she's offered an assignment to accompany some space marines on a possible bug hunt. But redemption and employment don't matter to her as much as cold, high-caliber revenge. Little do either Ripley or the meathead peanut gallery realize that she's the one who'll be dishing out most of it.

It took Cameron a while to convince Weaver that she wouldn't be playing, well, Rambo in space. As finally performed, her reprisal of Ellen Ripley belongs in the action heroine pantheon. Though she still wages a one-woman-war with an assault rifle and flamethrower, the stakes are obvious in her stuttered breath. She's going to exterminate these monsters or die trying, and she knows exactly where those odds lie. In a 2017 interview with Entertainment Weekly, Weaver broke the character down to her clinical core: "Ripley doesn't have time to try to be sympathetic, you know?" In "Alien," she was in over her head. In "Aliens," she's in exponentially deeper, and yet still goes sallying forth into the heart of darkness to save a single lost child. She's not tough, just calloused, and that makes her a lot more exciting to watch lock, load, and cry havoc.

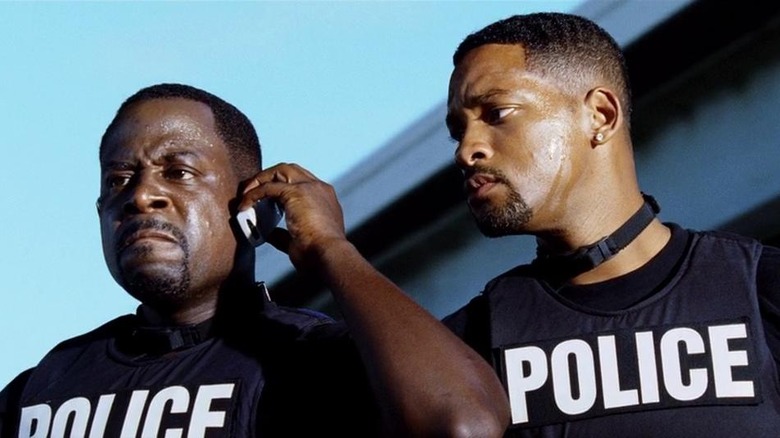

Bad Boys II

"Bad Boys" was a Jerry Bruckheimer and Don Simpson blockbuster made in a time when the superproducers were a genre unto themselves. The stars of the film had TV faces, both of them hasty replacements for Dana Carvey and Jon Lovitz. The director's biggest project to date was the "Got Milk?" campaign.

By contrast, "Bad Boys II" isn't just a Michael Bay movie. In many ways, it's the Michael Bay movie. In response to the critical savaging of Bay's reach for "Titanic" prestige, "Pearl Harbor," Bay made a $130 million manifesto that stands to this day: He'll wipe out the human race in exchange for a big enough pyro budget.

"Everyone deserves some dignity," Martin Lawrence says. It's a joke that Bay never stops laughing at. Morgue-fresh corpses bounce around during a car chase like barrels in "Donkey Kong." A throwaway line about rat sex pays off with an animatronic demonstration. Heart-to-heart banter is spiked with gay panic entendre and broadcast across a Best Buy so shoppers can properly sneer at genuine, human feelings. The shanty town chase from "Police Story" is restaged and re-energized with even more collateral damage. Moments after pulping a suspect under the wheels of the Miami-Dade Metrorail, Lawrence dares the gods once again: "This has to be the worst, most emotional cop week of my life." And that's before Lawrence and Will Smith invade Cuba with a splinter faction of government agents to save his sister.

"Bad Boys II" is the worst, most emotional cop week ever stained on celluloid. It's incredible, if you can stand it.

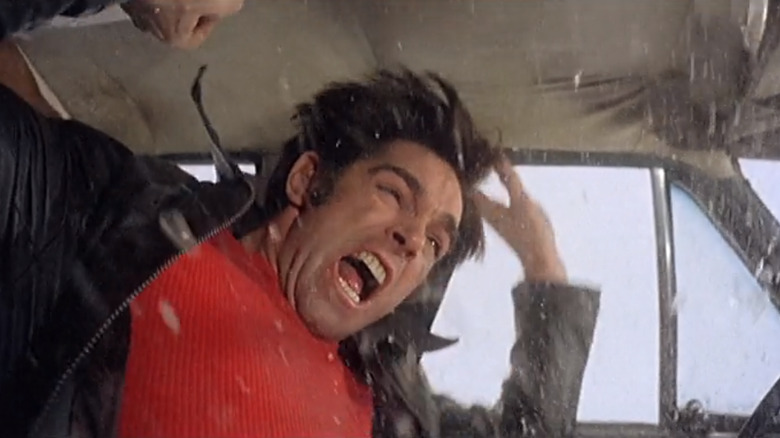

The Big Racket

The difference between poliziotteschi, the Italian brand of 1970s Eurocrime, and the "Dirty Harry" class of American procedurals that influenced it is right there in supercop Fabio Testi's first big act of police work. After observing a gang of bold-faced thugs assault, extort, and generally terrorize their way across Rome, he tails them to a remote meeting. Instead of stepping out with a cool line and cooler gun, Testi is cornered. The gang members beat in every surface that's beatable and tip his unmarked car over a cliff. Inside, two cameras keep rolling as Testi himself inverts, fighting to keep the broken glass out of his pretty face.

In poliziotteschi, violence is unrelenting and unapologetic, not to mention often dangerous both inside and out. Not even the supercops are safe. Why else, pray tell, would they be so driven to take the law into their own brass-knuckled hands? In "The Big Racket," there is no lip service paid to any alternative but vigilante justice. When Testi bumps against departmental corruption, he packs up his suede peacoat and Marlboro Reds and goes freelance, arming every victimized local he can find. The resulting war is among the subgenre's most visceral, but director Ezno G. Castellari never quite lets it satisfy. Even Testi, victorious, ends the film lashing out at nothing. Though the fascist pulp of Italo-crime may be an acquired taste these days, "The Big Racket" remains one of its smoothest flaming cocktails.

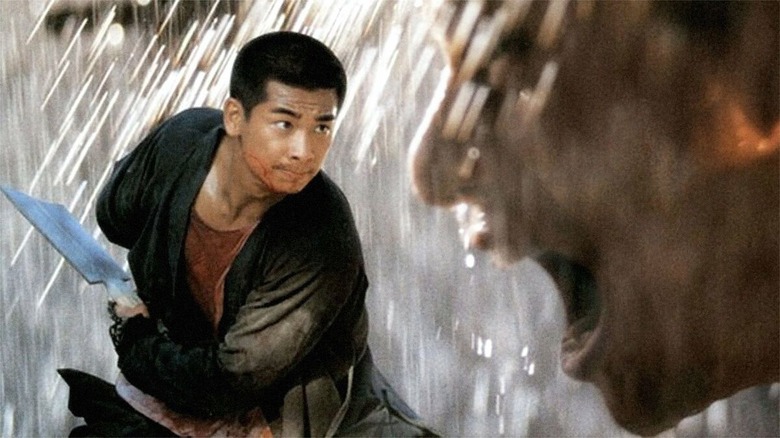

The Blade

Of the holy Hong Kong trinity formed by Tsui Hark, John Woo, and Ringo Lam, Hark is the toughest to classify. His best films include period action-comedies ("Peking Opera Blues"), martial arts epics ("Once Upon a Time In China"), and bullet ballets ("A Better Tomorrow III"). All of them are excellent, but none are definitive. To best represent that range, however, nothing beats "The Blade."

To update Chang Cheh's formative "One-Armed Swordsman," Tsui worked without a script and covered the difference with pitch-black brutality. For the sin of attempting to avenge his father's death, blacksmith Vincent Zhao loses his right arm to the same assassins who orphaned him. Instead of vowing revenge, he gives up everything and hides. For that sin, some random thieves break into his house, hang him upside down, and set fire to the place. Only then, with nothing left but anger and his father's broken sword, does Zhao start training to even the score. Cruelty is the rule, and if anyone forgets it, the naked corpses dangling in the streets will remind them.

In Tsui's hell, violence is subjective. The blinding swords aren't what kill, but rather the white-eyed faces behind them, disfigured with rage. Each fight is another scorching montage built around Zhao's unbeatable windmill strike. The camera keeps up with him to the blurry doom of his challengers. If they get lucky, they parry once. Then it's a spin, a forward thrust, a glint of steel, and blood staining the nearest shoji screen. The one-armed swordsman is just that good. So's Tsui.

Blade 2

Wesley Snipes' reps told him not to do "Blade." The offer landed with a thud in the superpowered lull between "Batman & Robin" and "X-Men." In a 2017 interview with Tom Power, Snipes repeated his bulletproof logic for taking the job anyway: "Because I've never seen a Black vampire that did karate before!"

The first "Blade" has its charms, chief among them the infamous blood rave, but "Blade II" finally cashed that check in full. The half-vampire slayer suddenly has bigger problems than textbook bloodsuckers. A new breed, part Nosferatu by the looks of them, has hit the streets. They've got "Predator" mouths, a hunger for humans and vampires alike, and a bone structure that makes staking them a pipe dream. Even when pinned with swords, they just disembowel themselves and escape. The only way to defeat them? That's right: more karate.

Director Guillermo del Toro, fresh from "The Devil's Backbone," lets his fairy-tale abominations shriek for themselves and shoots "Blade II" like an exceptionally gory fight movie. And Snipes, a black belt in multiple martial arts, comes to play. This is a movie star at the height of his powers and proud of it. Every one-liner, every vertical suplex, every blind catch of his trademark Oakleys is a perfect union of actor and character, one of the best to ever throw down on camera. Superhero cinema just doesn't get any cooler.

The Blues Brothers

The basis for "The Blues Brothers" is, ultimately, a "Saturday Night Live" sketch about Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi wearing bee costumes. When they ditched the stripes and became a genuine act, complete with a murderer's row of musicians behind them, they didn't even leave room for a punchline. These were two of the most popular funnymen in America showing off their blues-nerd version of a garage band on national television.

Somehow, that double-platinum-scoring side gig resulted in a two-hour-plus odyssey that's one of the least-classifiable films of its kind, whatever that kind is. A comedy? Musical? Chase picture? Yes and no to all of the above. That fish-nor-fowl mania is the result of first-time screenwriter Aykroyd turning in a phonebook-sized script that chronicled every last detail of the band down to the magical powers of its noble, unmarked steed, the Bluesmobile. Director John Landis, firmly established as a conductor of chaos on "Animal House," distilled his star's encyclopedia to its free-associative essence.

The dance numbers may be action-packed in their own right — just look at Aykroyd's legs go during "Sweet Home Chicago" — but the demolition derbies are literally record-breaking. 104 stunt cars were used in the production, necessitating a 24-hour repair shop dedicated to nothing but. Landis and his mad band filed for special dispensation to race down some of the Windy City's busiest streets at 100 mph. And that's to say nothing of the shuttered shopping mall the production repopulated for the express purpose of destroying. Between the sing-along soundtrack, the four-wheel mayhem, and the sense that a spring might fly loose at any second, "The Blues Brothers" is like spending two hours at the most dangerous county fair in the country. Not many action movies can claim the same.

The Bourne Identity

"Normally, the action is just a gratuitous thing," said director Doug Liman in an interview with Variety. "In the case of 'Bourne,' he was going to learn about himself in the action scenes." On "Identity," his first studio picture, Liman learned about himself in the action scenes, too. His free-associative style made schedules unnecessary and producers bright red. Such conflict would come to be something of a trademark, affectionately dubbed "Limania." But his work, and everything that copied it, speaks for itself.

Fistfights and car chases are equally frantic for bushy-tailed Matt Damon, 32 and looking at least five years younger. His skills, lost thanks to a bout of amnesia, come back as panicked reflexes. Inverting elbows. Drifting a Mini Cooper through oncoming traffic. Bringing a Bic pen to a knife fight. Using a corpse as an airbag to fall four floors and emerge more or less unscathed. The sequences are chopped up and screwed to match, sacrificing a sense of geography for adrenal urgency. Liman pays less attention to the punches than the tangling arms in search of a target.

Some may argue that Paul Greengrass improved on that style for the sequels by shaking the camera to the point of inducing motion sickness, but the DNA is all Liman's. The highest compliment paid to "The Bourne Identity" came from the competition. When James Bond needed a role model in a post-9/11 world, he took some lessons from Jason Bourne. "Casino Royale" could've justifiably made this list, but without "The Bourne Identity," there is no "Casino Royale."

The City Of Violence

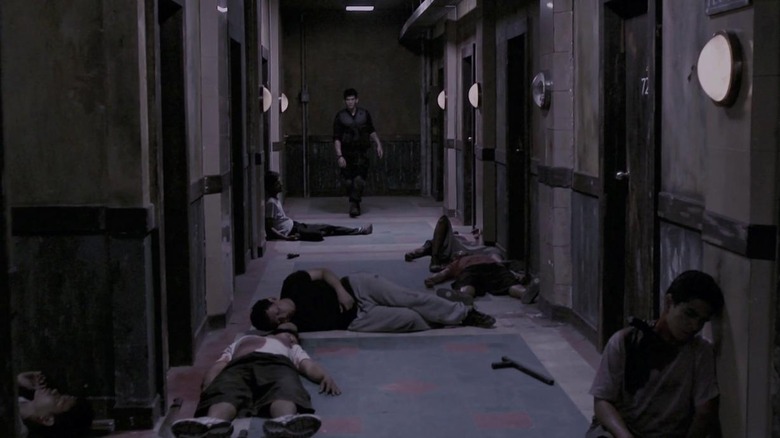

Pitching "The City of Violence" to Twitch Film, writer-director-producer-star Ryoo Seung-wan described it as, "taking characters from a John Woo or Chang Cheh film, [putting] them in a world similar to Roman Polanski's films, and developing Jackie Chan-style action inside that world." To the filmmaker's considerable credit, once you see the film, that makes sense.

Four estranged childhood friends reunite over the unusual death of a fifth. Three have gone respectable — police officer, math teacher, loan shark — and the fourth has gone dark, serving as the godfather of Seoul. For a while, it's an uneasy drama about roads not taken. Then, Seung-wan flashes back to the good ol' days, when the five of them would take on other, larger teenage gangs in stick-fighting brawls and end up buried to their necks when inevitably defeated. As the loanshark and cop, respectively, Seung-wan and stunt coordinator Jung Doo-hong accept the hard-boiled call of duty, investigating the fifth man's murder and maybe, just maybe, waxing nostalgic with their knuckles.

But a movie called "City of Violence" doesn't make this list because of its plot. Consider Doo-hong walking alone at night, passing a group of breakdancers. One worms toward him in silent challenge. The resulting street fight is all dodges, rolls, and repurposed poses. Doo-hong flees as soon as he can punch a hole in their hand-standing defenses, but doesn't get very far. Almost immediately, he's boxed in by three other themed gangs: hockey jocks, schoolgirls, and baseball players. The ensuing war —there's no other word for it — is a jaw-dropping spectacle of bodily motion. Doo-hong spins through it like a top, the inertia not played for Chan-brand grace but chest-caving brutality. And that's not even the biggest, best, or pulpiest fight in the "City."

Cliffhanger

Director Renny Harlin didn't think the Rocky Mountains looked intense enough to pass for the Rocky Mountains, so he moved the bulk of production to the Dolomite Alps in northern Italy. Whether or not that was the most practical decision, it's certainly a Harlin-esque decision, made for optimum brawn and outrageous scale. His "Die Hard 2" suffered for its human hero in outlandish peril. What he needed was a superhuman.

Sylvester Stallone was afraid of heights when they started shooting. And yet, for the most part, that's him up there, Rocky and Rambo dangling at 13,000 feet and shivering in a t-shirt amid alpine snow. The fallibility is baked into the script — the opening, in which Stallone's bulging bicep is no match for gravity, is as agonizing as ever — but it comes through in every anguished close-up, too. The difference between Schwarzenegger and Sly at their respective peaks was pain; while the former was more or less invincible, the latter hurt. At its best, "Cliffhanger" is Stallone returning to his "First Blood" roots after the Rambo sequels turned the character into a U.S. military recruitment poster.

Between Schwarzenegger and Stallone, Sly had the better 1993 at the box office, with this and "Demolition Man" sitting prettier than "Last Action Hero," but the bell had tolled for both muscle men. Stallone didn't have much more success in the shoot-'em-up business until "The Expendables" brought the old models out of retirement. Harlin attempted to mint Geena Davis as the first action heroine of the '90s — and she deserved that status after "The Long Kiss Goodnight" — but to no avail. At least "Cliffhanger" still stands perilously tall as one of the genre's last great analogue blowouts.

Coffy

"It was easy for him because he really didn't believe it was coming," says nurse-turned-vigilante Pam Grier to drug pusher number two, seconds after blowing a hole through the head of drug pusher number one, "but it ain't gonna be easy for you, because you better believe it's coming." This is the Grier allure in brief: It's impossible to miss her, but underestimate her at your own peril.

In her first solo act, Grier takes on the whole heroin trade. Using herself as both bait and trap, she lures in her prey with her Amazonian figure and ices them with million-dollar lines —"You gonna fly through them pearly gates with the biggest f***ing smile St. Peter ever seen!" — and whatever's on hand: a shotgun, a syringe of junk, one of the razor blades hidden in her hair. Director Jack Hill certainly put the exploitation in Blaxploitation — "Coffy" has more than a little skin and some of its violence, like an automotive lynching, toes the line of poor taste — but the film hasn't lost much of its empowered edge in the decades since its release.

Grier worked with Hill on the script, basing the title character on her own mother. Her stunt double, Jadie David, was the first Black woman in the business. Against the contemporary odds, Pam Grier became the prototypical action heroine, Black or otherwise, and she knew it: "I was creating the market for films about women fighting back and using sexuality," she tells The New York Times. And it all started with her double-barrel entrance in "Coffy."

Commando

In "Stay Hungry," Arnold was a discovery. In "Pumping Iron," Arnold was a novelty. In both "Conan" and "Terminator," he was an irreplaceable gimmick. What he was in "Commando" is printed right there on the poster: "Schwarzenegger" is attached to the title.

If there was any doubt that the decade's pre-eminent action star had arrived, they were allayed by the opening credits. The Austrian Oak enters carrying a chainsaw in one hand and a normal oak in the other. Everything that follows is best explained and excused by director Mark Lester's vow upon catching a screening of the competition, as reported by Empire: "We've got to have a bigger d*** than Rambo."

Without provocation, John Matrix is a teddy bear in lederhosen. Even baby deer love him. Kidnap his daughter, though, and he becomes a human wrecking ball. The only time he ever stops moving is when an entire mercenary team wrestles him to the ground and pumps him full of tranquilizers like an escaped rhino. But that's just a speedbump to a superhero. Matrix jumps from planes mid-flight and hefts phone booths mid-call. Milliseconds after crashing a convertible flat-out into a lamp post, he asks passenger Rae Dawn Chong if she's alright, answers for her, and steps out to dangle a villain off a cliff. The finale is a ten-minute middle finger to "First Blood: Part II," a one-man war waged off the California coast because Dan Hedaya's South American dictator tried to blackmail the wrong perpetual motion machine of violence.

With nary a second, squib, or sarcastic post-mortem wasted, "Commando" is the platonic ideal of '80s action and the arrival of Arnold Schwarzenegger, movie star.

Conan The Barbarian

Some actors are tailor-made for once-in-a-lifetime roles. Arnold Schwarzenegger, on the other hand, was too buff to play Conan. Director-cowriter John Milius didn't want a bodybuilder, he wanted a barbarian. His dogged belief in that unconventional leading man to slim down, to sell his bruise-purple dialogue, and to become his Conan turned pulp schlock into Wagnerian opera.

Schwarzenegger is not the eloquent brute found in the pages of Robert E. Howard's endless paperbacks. He is, however, the carnal hulk that Frank Frazetta painted on so many of their covers. Even demanding his god grant him bloody revenge is too much talk for Conan. "I have no tongue for it," he says. The Austrian accent makes his few words sound angry and alien, as if he's never had to speak before and hails from a world without the need to. He wanders the mystic wastes in search of sex, treasure, and revenge, the only languages he truly speaks.

And yet, when Schwarzenegger swings the Atlantean Sword, his impossible physique disappears. In the instant before the blade stains with blood, he's just two eyes white with wrath, a child stomping on anthills for blocking his way. No amount of warpaint can hide the softness of his face. This barbarian is in arrested development, an innocent tortured and rewarded by becoming a hedonistic killing machine, and Milius trusted the only man alive who could physically thread that needle. Arnold Schwarzenegger may not have become Conan, at least by literary standards, but, in his Olympic style, he managed an even greater feat: He made Conan become Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Crank 2: High Voltage

"Crank," Mark Neveldine and Brian Taylor's directing debut, ends with hero Jason Statham falling from approximately 6,500 feet in the air and landing on a Jaguar XJ6. Despite this, Lionsgate asked them for a sequel. Seeing the offer as an elaborate dare, the duo wrote another one. To this day, they don't believe the studio actually read the script.

Watching any given scene in "Crank: High Voltage" confirms their suspicions. This is, by Neveldine and Taylor's admission, the "Evil Dead II" to the original's "The Evil Dead." It's part remake, part perversion, part afront to the form. Instead of needing a constant supply of adrenaline to keep his heart beating, Statham requires regular electric shocks to keep his black-market replacement ticking. Energy drinks won't cut it anymore. This time, he'll need to, say, harness the lightning of a power substation, assume Godzilla proportions, and body slam his enemies into the nearest miniature warehouse. Everything old becomes new again, but much nastier; public sex with girlfriend Amy Smart becomes an acrobatic marathon session in the middle of a horse race. Statham, an anointed descendent of the '80s action icons, proves himself more game than the entire class. No other actor could sound so tough yelling at a dog walker to keep shocking his collar and look so silly shaking off the effects.

"Crank: High Voltage" remains a benchmark in vulgar action, the incredible product of two mad artists pushing prosumer cameras to new heights and newer lows. There have been whispers of a third "Crank" ever since (possibly to be shot in 3D, as Statham tellsMovies.ie) but the world may not be ready for that yet. It still isn't ready for "High Voltage."

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

"The martial arts film, after I got into it for months, I realized it was really musical," director Ang Lee said in an interview with Entertainment Weekly. "There's a certain innocence to it. You put logic aside for a while and go to that childhood fantasy land." He'd been dreaming about making his own wuxia film ever since watching warriors duel to the acrobatic death between bamboo trees in King Hu's "A Touch of Zen." When Lee finally got the chance, he wanted his warriors to duel on top of those trees.

Master Chow Yun-fat and student-to-be Ziyi Zhang float on the branches like they're swimming in the atmosphere. Their strikes and parries are natural extensions of the forest, the wind, the world around them. The two-and-a-half-minute sequence, the film's most famous for a reason, took Lee and "Matrix" fight choreographer Yuen Woo-ping two weeks to shoot. The rest of the film was only scarcely less grueling — in an interview with Time, the director says he didn't take so much as a half day off.

Lee's hellbent dedication paid off in one of the most beautiful action films ever made. It spends more time on close-up drama than contemporaries like "House of Flying Daggers" — Lee referred to the balance as "'Sense and Sensibility' but with kick-ass" — but the combined star power of martial arts royalty Yun-fat and Michelle Yeoh only makes the eventual clashes that much more potent. Winning 2000's best foreign language film Oscar for Lee's native Taiwan, "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" served as an irresistible ambassador of wuxia cinema to American audiences. It's just as easy to swoon over today.

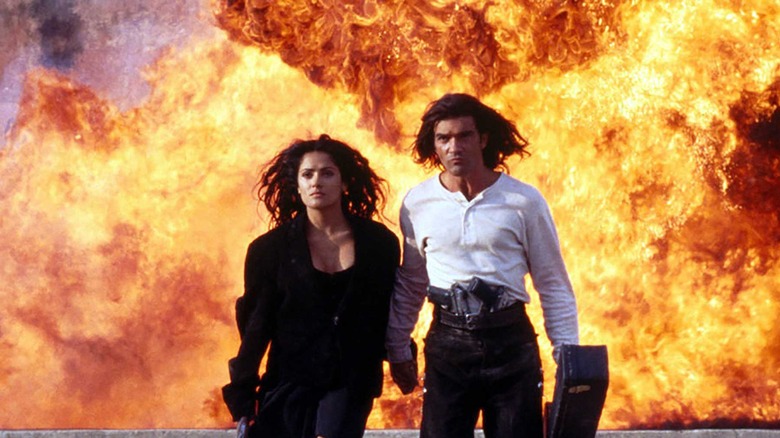

Desperado

A mariachi walks into a bar. The bartender tells him to put his hands up, because there's been word of a mythical avenger out for blood carrying a guitar case full of guns. The mariachi plays dumb until his guitar case pops open, then he fills his hands with spring-loaded pistols and ventilates the entire bar. In a single sequence, second-time director Robert Rodriguez earns his entire career, and first-time action hero Antonio Banderas earns his spurs.

"Desperado" is the unmistakable product of a young filmmaker with everything to lose. His first movie, "El Mariachi," cost $7,000. This direct sequel cost $7 million. Rodriquez spent most of it perfecting his brand of Hong Kong Tex-Mex gunplay. Banderas flicks pistols akimbo like 45-caliber bullwhips and dives backwards off rooftops so he can shoot behind himself on the way down. Guitar cases hide both rocket launchers and gatling guns. The great Danny Trejo brings knives to a gunfight and beats conventional wisdom, for a while. A shot-up ceiling fan falls just low enough to paddle a corpse's nose like a baseball card in bicycle spokes. Adobe, glass, and blood explode violently and often.

As Sergio Leone's "Dollars" trilogy is to Rodriguez's "Mariachi" trilogy, so is the Man with No Name to the Man in Black. Banderas talks more than Eastwood ever did, but when even your stammered pleas for non-violence are this ferociously charismatic, you let the gunslinger speak. When he finally teams up with local librarian Salma Hayek, making her Hollywood debut, they may well be the two most attractive human beings to ever share a burning rooftop.

Destroy All Monsters

"Destroy All Monsters" feels like the going-out-of-business sale for the kaiju cycle, and for good reason: It was the intended end for Godzilla. After ticket sales began declining, Toho rallied four franchise founders — director Ishiro Honda, producer Tomoyuki Tanaka, special effects pioneer Eiji Tsuburaya, and composer Akira Ifukube — and sent off the big guy in style.

Just when all the world's monsters (and most of Toho's suits) have been safely contained, aliens hypnotize them into rampaging anew. No metropolitan center or miniature skyline is safe — except, that is, for Tokyo. What are those mod visitors from outer space really up to? Though the terrestrial investigations of the United Nations Science Committee have their charms, playing at times like a soap opera with ray guns, the building-sized characters are the stars of the show.

After wiping out cities solo, the monsters reconvene for a no-holds-barred royal rumble with King Ghidorah. Mountains are moved. Roars of every pitch ring out. Limbs, tails, and tripod necks are bent every which way but healthy. It's like watching a kid dump out their entire toy box and start smashing their favorite playthings together in the most giddily destructive way possible.

Dhoom 2

Master thief Hrithik Roshan enters the film skydiving, an X-marked spot over the blank Namib Desert. The only civilization below is a train, just four compartments long. Onboard, the Queen of England rides with her grandchildren and crown. How will he get inside? How will he avoid detection? Before a third suspenseful question can be asked, the prize disappears and Roshan peels off his flawless queen disguise. Not that he gets away scot-free, of course —the criminal genius still has to backflip off the caboose and sand-surf between bullets.

The first "Dhoom" was Bollywood's answer to "The Fast and the Furious," a flashy cops-and-gearhead-robbers story. In just one sequel, director Sanjay Gadhvi outpaced the Americans by three or four. Cool is the rule, leaving all other logic and the laws of physics at the door. This is a film about the prettiest people in the world out-heisting each other in the prettiest places in the world, from India to Rio de Janeiro. How does Roshan steal a diamond from a heavily-patrolled art gallery? By posing as a Greek statue and steering a diamond-snatching Roomba along the black stripes in the floor, of course. When making an escape via sewer, he doesn't crawl out of a manhole. He rockets through it on a jet of water and lands on rollerblades. It's everything "Fast and Furious" is now synonymous with, only wilder, produced decades earlier, and with exhaustingly choreographed dance numbers thrown in as a bonus. That's modern Bollywood action at its best.

Die Hard

John McClane is barefoot. It's an offbeat detail in an offbeat action movie. At the tail end of a decade built on superheroes without capes, here's an unremarkable, if athletic, physical specimen given immediate handicap. Not only is he outnumbered, outgunned, and arguably outwitted, but he's going to get blisters while he dies trying to save the day.

"I think John McClane is the opposite of a superhero," said Bruce Willis in a contemporary interview. "He's capable of being afraid, of making mistakes, of feeling pain." When McClane isn't doing one or multiple of those things, he's thinking, planning, and picking glass out of those bare feet. "Die Hard" is less like its slam-bang contemporaries than a cat-and-mouse thriller between Willis and Alan Rickman, then new to the screen. The jaunt of it is what hooked John McTiernan, fresh from directing "Predator," a subversive take on those slam-bang contemporaries. He had no interest in the project when the villains were terrorists, but once this was changed to thieves posing as terrorists, the director found his fun.

It's difficult to discuss "Die Hard" in the shade of its now-legendary action movie status, but every viewing gives away another ingenious brush stroke. A push from cinematographer Jan de Bont. A texture from production designer Jackson DeGovia. A line from screenwriters Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza. This is the result of an all-star team working at the top of their respective games when lightning happened to strike. "Die Hard" was, is, and forever shall be that good.

The Dirty Dozen

Action is a distant proposition at the start of "The Dirty Dozen." It's merely a strategy scribbled in the second-person and passed around ornate offices in tasteful manila folders. For all the decorated brass milling about, only Lee Marvin seems to recognize the stakes of the far-away game they're playing: "I never went in for embroidery, just results." But he's just the kind of bastard they need to train the absolute scum of the earth — or at least of the U.S. Army.

The operation, a take-no-prisoners assault on a Nazi retreat in occupied France, doesn't kick off until the last 40 minutes of the two-and-a-half-hour film. Until then, it's summer camp fun with some of the toughest tough guys to ever share the screen, all of whom are playing death-row convicts. John Cassavetes. Clint Walker. Telly Savalas. Charles Bronson and Jim Brown, both of whom have runners-up for this list on their respective CVs. That's not even counting Ernest Borgnine, George Kennedy, and Robert Webber back at base. But those three play authority figures, and director Robert Aldrich would just as soon pie them in the face as straighten their medals. This one's for the bad guys, made good only by the worst guys in modern history. There's so much bonding with the squad that it's easy to forget that they've been recruited explicitly to die.

When the grenades start rolling, "The Dirty Dozen" makes up for lost time. There was never going to be any mercy, but Aldrich leaves out the valor, too. These scoundrels have been forcibly enlisted to do what needs to be done, screams and all. War is truly hell in "The Dirty Dozen," and these guys have home-field advantage.

District B13

"District B13" borrows liberally from the "Escape From New York" playbook. In the near future of 2010, the French government gives up on crime-ridden Banileue 13 and seals the entire neighborhood shut. When even the police are too scared to cross the border, who will track down the missing neutron bomb stolen by the meanest gang in the district? In lieu of Snake Plissken, director Pierre Morel substitutes the founder of parkour.

David Belle moves like a ping-pong ball. His discipline, derived from the French word for "route," bounces him through the tightest apartment blocks in the world like he was running a 5K. Gang enforcers bum-rushing him? Just kick off the wall and spin over their heads. Sprinting toward a dead-end, sixth-floor balcony? Just hurl your body over the edge, catch the rail, and swing onto the fifth-floor balcony below. Running out of roof? Just jump and get ready to roll if and when you land. Parkour has since grown into self-parody — watch a recent run on YouTube and try to count the unnecessary flips — but this is as primal as it gets. Belle has to get from A to B, often with armed resistance in between. On the way, he becomes Bruce Lee's philosophical water, making his way through cracks and letting the landscape shape him.

Belle's work was so influential to the genre, even before his breakthrough here, that, as the Tribeca Film Festival discovered, Sam Raimi briefly considered casting him as Spider-Man. It's not hard to see why.

Drunken Master II

In "Drunken Master II," fighting is another means of communication. When drunken boxer Jackie Chan asks for the price of fresh red snapper, fishmonger Felix Wong challenges him to fight for a bargain. Chan outclasses him, but insists it's a draw to dignify his opponent. Even in less friendly battles, like when Chan brings a sword to a spear fight with director Lau Kar-Leung in the cramped space beneath a parked train, the stakes are defeat, not death. Their abilities so proven, Lau eventually recruits Chan to his cause. This respectful tone gives the entire film the tone of an exhibition match, Jackie Chan versus the world.

Chan fends off a small army of hatchetmen with a bamboo pole as long as he is tall. When it frays, he keeps using it as a natural cat o' nine tails. When all seems lost in a street fight, he smashes two bottles of hard liquor together like Stone Cold Steve Austin and turns the tables. A little of the "good stuff" — unidentified, save for the skull on the label — lets him defy gravity, bent backwards and teetering past the point of no return for any mere mortal. Chan's signature drunken fist style is millennia old but somehow tailor-made for him. His gift for practical comedy is folded into every surprise blow, cock-eyed dodge, and sloshed smile at the challengers who can't keep up.

There's a case to be made for "Drunken Master II" as the ultimate Jackie Chan film. The first two-thirds bask in his boyish charm; he's still a teenage show-off at 40. The last third, which Chan fired Lau to direct himself, is another trademark test of human stamina, perhaps Chan's most exhausting. He chugs ethyl alcohol like it's a video game power-up and punches out the vomit, soon racing the camera's 24-frames-per-second. In the end, Jackie Chan literally rakes himself over the coals for our entertainment. There are metaphors, and then there's "Drunken Master II."

Eastern Condors

Drop John Rambo into the jungles of Vietnam and, sure, he'll cook up some impressive anti-infantry measures. Branches sharpened into spring-loaded spikes. Camouflaged pits of death. Caking himself with mud for the perfect surprise chest stab. But drop martial arts legend Sammo Hung in there instead and he'll be launching palm stems like bullets and climbing trees with only knives in no time.

"Eastern Condors" is Hong Kong's answer to "Rambo: First Blood Part II" by way of "The Dirty Dozen." When it seems that the Viet Cong might locate an abandoned American cache of heavy artillery, Lieutenant Colonel Lam Ching-ying is charged with assembling a team of expendable-enough soldiers to blow it up. Should they survive the mission, the 12 lucky prisoners will walk free as rich citizens of the United States. In the grand tradition of men-on-a-mission cinema, very few do.

Losing 30 pounds for the role, Hung sacrificed his usual beach ball buoyancy for stone-faced resolve. That may be a turnoff for fans of his lighter romps — see "Wheels on Meals" below — but it gives this film an uncharacteristic bite. Hung still bounces across the screen, but only to stuff grenades in enemy mouths. Backing him up is a murderer's row of martial arts excellence. Three Dragons brother Yuen Biao. "Matrix" choreographer Yuen Woo-ping. Director Corey Yuen. Stunt coordinator Yuen Wah. Kickboxing champion Billy Chow. With a deck that stacked and a director this fearless, "Eastern Condors" is the best Rambo movie never made.

Elite Squad

Two rookie cops stake out some dirty superiors from a balcony high above a block party. They watch the proceedings through a sniper scope, not to kill, but simply to get the most damning view of their fellow public servants collecting his latest gang pay-off. After a few minutes of study, the officer holding the rifle opens fire anyway. The muzzle flash freezes. The shot rings into nothing. Brazilian special police captain Wagner Moura speaks purpose into the silence: "In Rio, every cop has to make a choice. He either turns dirty, keeps his mouth shut. Or he engages in war."

Those two rookies chose the hard path, not knowing that, in these favela battlegrounds, both ways end about the same. If you're corrupt, you're corrupt. If you're honest, that'll just curdle into eye-for-eye cruelty. Director José Padilha presents the resulting brutality of BOPE, a SWAT team's SWAT team, as-is. Critics at the time called it pro-fascism, but that implies enough hope to present a solution. This is a vicious cycle of security begetting paranoia and guns begetting bigger guns. Only the most damaged souls make it through BOPE training.

But even that's too fine a point for Padilha. He directs like he's got one hand on either side of the audience's head, dragging them from one sanctioned massacre to the next. Alien-lit alleys, all jaundiced orange and moldy green, blur together into a nightmare labyrinth of shaky, sweaty violence. Few action films are this agonizingly present, whether or not the audience wants to look away, whether or not any shell casings are hitting the floor — Moura's ulterior objective, to find a worthy replacement, is just as nauseating as the daily raid.

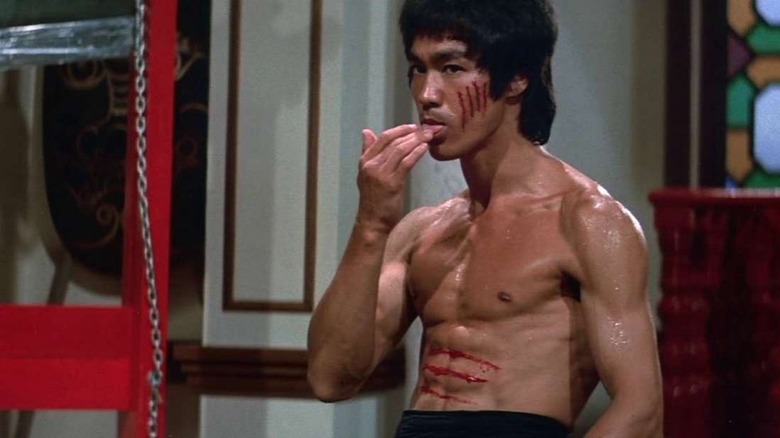

Enter The Dragon

A challenger, arrogant and foolish to the audience that knows better, asks Bruce Lee to explain his fighting style. "You can call it the art of fighting without fighting," Lee says. Like the rest of his lines, it's a mix of preternatural calm and igneous intensity. The smackdown is imminent. Lee offers to sail with his foe to a nearby island for a proper bout. The challenger obliges, getting into the dinghy first. Lee unhooks the line and lets the would-be enemy drift. Fighting without fighting.

The enduring majesty of Bruce Lee is that, even when he was truly fighting, it didn't look like fighting. When he bounces from toe to toe, that's just his body's natural idle state. He rarely seems to strike first, if only because his reactions are faster than anyone else's action. A half-century of disciples and knock-offs later, nobody moves on screen like Bruce Lee. Just as impressively, nobody acts like him, either.

"Enter the Dragon" was pitched as Lee's international debut. He died six days before it opened. That tragedy makes the film something else, something unbelievable — it's no coincidence that director Robert Clouse and company shot it like a comic book. It's surviving proof of a world record attempt, a shot at being the best action star alive by a martial artist with few runners-up; a hungry Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung show up only for the honor of catching Lee's hands. Beyond his physical prowess, Lee fought to make room for his philosophy. "Enter the Dragon" is a case for the man, myth, and legend. By the time he kicks a dummy of Shih Kien so hard that it seems to jump-cut clean out of the film, it's simply an accepted power of Bruce Lee. And that's when it becomes clear that "Enter the Dragon" is not just an attempt at greatness; Lee really was the best.

Escape From New York

"About an hour ago, a small jet went down inside New York City," says Lee Van Cleef, aged into his own monument. "The president was onboard."

"The president of what?" asks Kurt Russell, erasing his Disney career in a single line. Gone is "The Computer Who Wore Tennis Shoes." In his place is Snake Plissken, what you'd get if the world's top minds were tasked with designing the world's coolest-looking guy. The eyepatch. The give-a-damn beard. The outfit, all urban camo, cracked leather, and classic black. He looks so dangerous, in fact, that Russell accidentally scared off some street toughs by stepping around the wrong corner.

That one line — really, any one line — from Russell sets him apart from most of his action star peers. In an era when ego signed most contracts, he's an actor first. Action hero? That's not his problem. It's what keeps a character named Snake, a character who looks like that, from tripping into self-parody. Russell would put that fearless gift to most potent use in "Big Trouble in Little China," his fourth collaboration with John Carpenter.

And what to say about Carpenter? As likely the most remade director of all time, his influence is hard-wired into every genre he touched. Horror will forever be his legacy, but it's "Escape From New York" that changed dreams. Just as "Blade Runner" would the following year, Carpenter and co-writer Nick Castle's comic-book vision of a society that's not quite post-apocalypse, but rather mid-apocalypse, gave the genre a never-before-seen peek at the End, capital-E. Almost a half century later, for all its imitators, nothing beats the original, and nobody beats Snake.

Fast Five

Everything great about "Fast Five" — and the exponentially more outlandish sequels that followed — can be factored back to the arithmetic of its climactic chase. Universal told writer-producer Chris Morgan to recalibrate the franchise, shifting the focus away from hot rods and toward heists. So, how would the grease monkey heroes of "The Fast and the Furious" pull off a heist? By strapping a bank vault to a car and driving away with it, of course.

Brothers in blacktop Vin Diesel and Paul Walker have run out of road. The only way to clear their names and start fresh is to steal $100 million from a Rio de Janeiro crime boss. So, in what has since become a proud series tradition, the duo recruits any past racer that will answer their calls — Jordana Brewster, Tyrese Gibson, Ludacris, Sung Kang, and Matt Schulze — for the ultimate job. And then there's the opposition. Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson bulldozes his way into the only blockbuster franchise amenable to pro-wrestling soap and makes himself at home, treating every face-off with Diesel like it's their last promo before a title match. Johnson is at his best playing heel, and here that means visibly wanting to kill everyone else on screen and selling lines like "We don't ever, ever let them get into cars" like they're Shakespeare.

Director Justin Lin was born to drift what infamously began as a nitrous-poisoned "Point Break" riff through the looking glass. The first four films in the series might as well be unrelated. From here on out, though, they're all sequels to "Fast Five," but none are better.

First Blood

The legend was printed with "Rambo: First Blood II." There is no greater iconography of '80s action in America than Sylvester Stallone, shirtless and rippling, with a belt-fed machine gun under his arm and a bandana around his forehead. The immediate (and compounding) increase in carnage across the Rambo franchise almost disqualifies the original as an action film by contrast. But take it from the man himself: "I think 'First Blood' is the best action film I've ever done," Stallone says.

Three "Rocky" films deep, Stallone hadn't found steady footing outside the ring. The opening scene of "First Blood" takes his underdog charm and carves it into a jagged edge. As the boxer, circumstance was his curse. As the Vietnam vet who finds out he's the last of his platoon, the curse is continued existence. The last flicker of his humanity is snuffed out with the bad news. After that, he's just a walking landmine. To say he's uncomfortable in his own skin would imply that he still recognizes himself as a creature covered in it.

"First Blood" is a dangerous movie. The police station torture. The motorcycle escape. Rambo's brutal regression into living camouflage. Every scene shudders with the same queasy tension. There are no heroes or villains here, just establishment bullies and an unwell killing machine. Stallone considered the part "a career killer," and it's easy to see why. Without his innate, beat-the-odds charisma, the character might as well be a slasher. As is, this is still one of his best performances, heartbreaking and brutal by the same flick of the knife. "First Blood" still ends with Stallone underdressed, machine gun in hand and bandana on head, but this Rambo isn't a cheerleader. He's all Frankenstein's monster.

Five Deadly Venoms

No list of action essentials would be complete without an appearance from the Shaw Brothers. Runje, Runde, Runme, and Run Run Shaw founded Unique Film Productions in 1925. By the 1960s, their sprawling studio complex was turning out a new movie every 10 days. The sheer quantity, not to mention quality, of their films meant the company defined the blazing speed, eye-popping vibrance, and acrobatic choreography of martial arts cinema for generations to come. That sweeping ShawScope logo still means just as good a time as it always has.

And "Five Deadly Venoms" may be its best time. Bright-eyed student Chiang Sheng is tasked by master Dick Wei of the Venom Mob to seek his five previous apprentices, stopping any of them out for blood over a forgotten fortune. Trouble is, the men were famous for their masks just as much as their fighting styles — Scorpion, Lizard, Toad, Snake, and Centipede — and that's pretty much all anyone knows about them. Before he can challenge them, Sheng has to play detective and find them. It's an odd structure for this kind of film, but one that pays off in unspoken history; the connections between the Mob feel genuine because the actors had been honing their craft together since childhood.

The battles are gymnastic enough — Philip Kwok's specialty is literally defying gravity — but more intimate than incredible. The six fighters, choreographers all, land their blows by brutal metronome, their clashes landing somewhere between dance number and tumbling act. Despite their Peking Opera masks, the drama is grounded in the bruises. When Kwok and Sheng both stand up on the walls, parallel to earth, awaiting the next strike from a surprising foe, the lunacy never registers, only their barely restrained power.

Freebie And The Bean

"Could you send a tow truck please to 618 Elm Street ... hold it," says detective James Caan, pausing to check the number on the door. "It's the third floor, apartment 304." On one side of him, the mile-wide nose of a '72 Ford Custom 500 hangs through a highway-view window. On the other, partner Alan Arkin collapses in an ulcerous heap.

"I shot the film partly in a Tom and Jerry style," said director Richard Rush to Money into Light, with an asterisk the size of a bullet hole, "The audience is laughing and enjoying themselves and suddenly Freebie would drive around the corner into a marching band of kids." That split-personality was Rush's reaction to contemporary TV, dopey sitcoms interrupted by newsreels full of carnage, and it's only gotten more jagged with age. For every high-flying trapeze act — Caan bucking a dirt bike across gridlocked cars to the tune of Dominic Frontiere's ragtime piano — there's a wincing comedown — the two cops unloading four pistols into a single suspect cornered in a bathroom stall. They may think they're Tom and Jerry (and they do, judging by the driving) and the world may occasionally bend to their slapstick will, but Arkin and Caan are merely the bickering byproducts of a system that couldn't care less about justice or consequences.

In terms of this list, what tipped the coin toss between this and Rush's follow-up, "The Stunt Man," is history. Along with Peter Hyams' more openly nihilistic "Busting," which came out the same year, "Freebie and the Bean" forged the buddy cop formula. The city-wrecking action. The wall-to-wall banter. The begrudging love of men who'd just as soon strangle each other as hug. All its descendants did was blur the line between cartoon and carnage. But, to Rush's credit, the car chases never got better.

The French Connection

When William Friedkin first saw "Bullitt," a fair swap for any movie on this list, he loved it with an asterisk: The climactic car chase sent Steve McQueen careening down conspicuously underpopulated San Francisco streets. For his own hard-driving cop story, Friedkin wanted obstruction.

"The French Connection" is nothing but. Ostensible hero Gene Hackman is a racist boozehound with a badge. Ostensible villain Fernando Rey is a charming continental-type. In this New York, a shadow-and-soot wasteland, nothing is ever easy or clean. And so it goes for the legendary chase between Hackman's Pontiac and the hijacked D-Train. For one thing, the detective can't even catch his quarry. He's just keeping up until it runs out of rail. That train also has a lot more rail than Hackman has road. Stunt driver Bill Hickman drove the 26 blocks at almost 100 miles-per-hour without a single permit. The motorists and pedestrians seen lunging out of the way might as well be dodging a low-flying comet. An actual crash, the result of a mistimed swerve between star and stunt driver, was worked into the finished sequence, further blurring the line between maverick recklessness and criminal negligence.

Friedkin's trophy is right there in the bodywork. In six-odd minutes, he turned a Pontiac into the lunar surface. He'd go for his own gold a decade later with "To Live and Die in L.A.," another hard-driving cop story that hinges on a spectacularly ill-advised car chase.

The Fugitive

"The Fugitive" is such a good action movie that its actual plot doesn't matter. Why is vascular surgeon Harrison Ford framed for murdering his wife? How does the FDA factor into it? Who hired the one-armed man? Many people who've seen and enjoyed "The Fugitive" multiple times on basic cable couldn't answer these questions. That those answers are irrelevant is a testament to director Andrew Davis, a ringer among journeymen.

In "Code of Silence," Davis coaxed a career-best performance out of Chuck Norris. In "Under Siege," he did the same for Steven Seagal. That movie in particular caught Ford's eye. Here was a director who treated action as a character piece, even with the most famously stiff stars in the business. With bona fide actors like Ford and two-time collaborator Tommy Lee Jones at his disposal, Davis could work wonders. With savvy assistance from "Die Hard" scribe Jeb Stuart, the only writer to pitch Jones's U.S. Marshal as a sympathetic antagonist instead of outright villain, he did.

"The Fugitive" isn't essential action cinema because of the $1.5 million train derailment or the $2 million dam jump — both all-timer sequences both — but because it's an impossible race. Both Ford, an unstoppable force for truth, and Jones, an unstoppable force for justice, are worth cheering for, but if they ever close the half-stride gap between them, both lose. No truth. No justice. It's Hitchcockian tension as a spectator sport, only holding taut for two-plus hours because of the eminently human athletes involved. Davis' talent with actors paid off in literal gold — Jones earned an Oscar and a Golden Globe for his performance.

Full Contact

There's a certain sterility to the "heroic bloodshed" of Hong Kong action films. Remove the squibs and wave away the stagnant gun smok, and the emotions become primevally pure. Honor split by the long arm of the law. Unnatural foes forced to admit their mutual respect for each other, if not die for it. If there is romance, it's chaste or downplayed in favor of the real passion: male bonding that unfolds between bullets.

Ringo Lam took the foundation laid by John Woo's "The Killer" and ran it through the gutter with "Full Contact," a gleefully scuzzy Harley ride through Hell. Chow Yun-fat is introduced smoking, not for the first time on this list, but here he holds his cigarette with fingerless gloves. His other hand is busy flipping a butterfly knife. He's a bad boy in a bad crowd, but not so bad that he won't pull a heist with the buddy who went into debt to properly bury his mother. When that buddy shoots him in the chest, steals his girl, and leaves him for dead, all Chow can do is even the score.

Chow rolls out of the blue Bangkok haze like a Zen demon, hard-rock screaming out the emotional toil he refuses to give away. Simon Yam, a psychopath in snakeskin, has no patience for subtlety, disarming victims with magic tricks before turning his handkerchiefs into switchblades. In Lam's eyes, their confrontations are nothing short of an MTV-style apocalypse; cameras race down the trajectory of the most destructive nine-millimeter missiles in film history in a very early display of bullet-cam.

The General

"We eliminated subtitles just as fast as we could if we could possibly tell it in action." That might as well be the first commandment of the action genre, acrobatically carried down the mount by one of its first heroes, Buster Keaton.

"The General" could just about get by without subtitles. Ace engineer Keaton loses the love of his life because he's not a military man, but fate intervenes when the second love of his life, the titular locomotive, is stolen by an enemy regiment with the first love onboard. All that matters is that Buster has a train to catch and an audience to entertain, both at any cost. As co-writer, co-producer, and co-director, Keaton insisted on using the real deal even for crashes, resulting in the single most expensive shot in the history of silent film. When trains aren't crashing, they are Keaton's steam-powered jungle gyms. Jumping between cars, leaping aboard at speed, playing chicken in reverse — this is Keaton writing the book on locomotive action. But what immortalizes him far beyond a century of imitators is Keaton's single-minded disregard for personal safety, let alone a second take. The film's most infamous example goes by almost unnoticed. Hugging the very-much-moving cowcatcher, Keaton hurls one railroad tie into another still lodged in the track ahead. They both bounce into the grass harmlessly. If they hadn't, or if he had missed entirely, the train would've derailed with him as a hood ornament. But wow, what a gag.

Contemporary reviews complained that "The General" wasn't as funny as Keaton's previous films. Little did they know that he wasn't making a comedy — he was perfecting the action blockbuster.

The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly

Six eyes. Three guns. One stash of pilfered Confederate gold. "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly" ends on mythically simple terms. So, too, does the Man With No Name. When director Sergio Leone started his landmark trilogy with "A Fistful of Dollars," he had the producers of "Yojimbo" crying plagiarism in one ear and star-to-be Clint Eastwood complaining about dialogue in the other. By the time that Man, simmered down to his reluctant essence as "The Good," marches into Sad Hill Cemetery for one last draw, Leone is speaking a language entirely his own.

In cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli's mile-wide frame, the duellists seem no taller than the tombstones around them. Up close, their eyes are big as gun barrels and just as hollow. Greed and survival are all that's left, urges twitching out to the trigger fingers. Composer Ennio Morricone fills in the unbearable stillness with one of the most iconic themes in cinema. This confrontation, not to mention the rest of Leone's flourishes, became shorthand not only for spaghetti western action but also the American myth. That's quite a legacy for an Italian director faking Mexico in a Spanish graveyard.

Hard Boiled

There is no greater entrance in action cinema than pounding a tequila slammer, gasping down cigarette smoke, and launching into a jazz clarinet solo. Then again, there are few, if any, action heroes greater than Chow Yun-fat's aptly nicknamed Inspector Tequila.

"Give the guy a gun and he's Superman," says one of his departmental critics. "Give him two and he's God." In Tequila's defense, when he's sliding down banisters and popping off akimbo Berettas, he bears a certain resemblance to the divine. Director John Woo, in his last hurrah before leaving Hong Kong for Hollywood, wanted to glorify cops instead of criminals for once. Instead of the soulful Triads from "A Better Tomorrow" or the conflicted hitman of "The Killer," this is his ballistic ode to the cinematic supercop. Even Tony Leung, Chow's met-match on the other side of the law, is an undercover officer. But, given that Woo started shooting a completely different movie and writer Barry Wong died partway through production, the plot is just yarn connecting a few bullet-shredded Polaroids.

As the apotheosis of Woo's 9-millimeter ballets, "Hard Boiled" grazes the absurdist sublime. Firefights aren't firefights, but volcanic obstacle courses for the cast and crew to dive through. High-tech weapons caches are hidden beneath hospitals. The virtuous wage war with a baby in one hand and a pistol in the other. A three-minute long take of Chow and Leung clearing out an entire ward of terrorists, untouched by the groundswell of digitally-assisted long takes that have cropped up since, only slows down because of damnable reality: the actors ran out of blanks and needed a moment to reload. There are tighter and grander works in Woo's filmography, but none so foundational; action cinema still kneels before "Hard Boiled."

Hard Target

For the 25th anniversary of his first American production, John Woo got honest with The Hollywood Reporter: "In 'Hard Target,' I was too ambitious and tried to do everything in one film." Surfing a motorcycle at speed for better aim. Holding a pistol upside down and unloading an entire magazine by index finger. Punching a snake unconscious and biting off the rattle to use it as a sentient booby trap. It's easy to sympathize with Woo's maximalist remorse. At least, it would be if he didn't have the perfect action figure to play with.

Jean-Claude Van Damme's claim to fame has always been his movement. The flying kicks. The wincing splits. The hip-heavy dancing. Hot off doing his best Schwarzenegger in "Universal Soldier," the budding star finally found a true patron in Woo. World-class heavies Lance Henriksen and Arnold Vosloo, as well as an allegedly Cajun Wilford Brimley, act enough for everybody. The rest belongs to Van Damme. Decked out in head-to-toe denim, plus or minus a black duster, his neo-western drifter saves words for the important things, like bad gumbo. His greasy mullet only underlines his grace, flowing in tune with every roundhouse. By the time he descends on a pelican-shaped parade float in slow-motion, pump shotgun spitting fireworks, Van Damme has outgrown and upstaged the ever-more-concussive mayhem surrounding him.

After "Hard Target," Woo's style ballooned and distorted through the American looking glass, reaching its operatic peak with "Face/Off." A case could easily be made for including that film on this list. The Gonzo Olympics between Nicolas Cage and John Travolta are certainly showier than anything here. But Van Damme belongs to the older school of Woo heroism, and he never got a better showcase than his time with the master.

Hard Ticket To Hawaii

What sets Andy Sidaris apart from most exploitation filmmakers is his innocence. "We don't hold women hostage, or slash their throats," he explained to DVD Talk, "I see movies that are so despicably mean-spirited that I can't believe them." Expletives rarely hit harder than "hell" and "damn." When blood is spilled, it carries all the severity of cherry cobbler. The standard arsenal is Q-Branch by way of Toys R Us, showcasing the latest in taping-bombs-to-remote-control-things technology. The standard cast may be a who's-who of Playboy and -girl centerfolds and yes, they may be more naked than clothed, but Sidaris always cuts away before things get too hot or heavy.

The best argument for Sidaris' oeuvre is "Hard Ticket to Hawaii," the only action film to invoke Chekhov's mutant snake. Store-brand-DEA agents Dona Speir and Hope Marie Carlton — well, one's really in witness protection, though both are also posing as island-hopping couriers — catch wind of a plot to swap diamonds for drugs and flood Molokai with junk. The only way to take the operation down is with a lot of shameless nudity and some of the most ludicrous action in B cinema. Consider the following:

"Man, he must be smoking some heavy doobies," marvels agent Harold Diamond as a skateboarder rolls by in a handstand. When the assassin-in-disguise rolls back again, he's armed with both a double-barrel shotgun and a blow-up sex doll. Diamond and his partner Ronn Moss respond by punting him in the air with their Jeep and shooting him at point-blank range with a bazooka. In other words, standard operating procedure in Sidarisland.

Hero

In "Hero," Jet Li and Donnie Yen stop just short of dueling each other. They stand silently across a courtyard, letting the strings of a guqin and the percussion of the rain speak for them. At the same time, they close their eyes. These are masters, after all. They can run the entire fight in their minds, meeting each other blow for predicted blow. It doesn't flow any more or less incredibly than any other showdown in "Hero," even as Yen hangs upside down, attacking with his spear, and Li retreats halfway up a pole to dodge. Like everything else in Yimou Zhang's half-historical epic, it's a tale within a tale, exaggerated only for the emotional truth.

Emperor-to-be Chen Daoming takes no chances after three killers make unsuccessful attempts on his life. But Li, playing a prefect known only as Nameless, claims that he's slain those assassins, and shows their abandoned weapons as proof. With each convincing account of their defeat, the king allows him to get a little closer, even though this protector may really be the next assassin in the line. It's "Rashomon" with the objectivity of inherently subjective accounts replaced by the believability of inherently unbelievable feats of martial artistry. And with a cast of wall-to-wall titans — Li, Yen, Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung, Zhang Ziyi — it's easy to buy the impossible. There are few more moving images in wuxia cinema than Li and Leung chasing each other across a mirror-still lake, traveling too quickly to break the surface, and it's not even the most moving image in "Hero," at the time the most expensive Chinese film ever made.

Highlander

"Highlander" opens with a crawl narrated by Sean Connery and a power ballad by Queen. Not a minute into the film proper, director Russell Mulcahy hurtles the camera from upper deck to upper deck of a boxing match using a Skycam rig usually reserved for televised sports. Here, it's to give proper weight to Christopher Lambert's first close-up, shone across the eyes like Dracula.

If there's anything to be said for subtlety, "Highlander" doesn't bother saying it. Mulcahy, a veteran of Duran Duran music videos, only has time for fog and shadow and rotoscoped lightning. It turns screenwriter Gregory Widen's darkly romantic tale of swordfighters cursed to duel forever into heavy metal fantasy. Every clash is constructed like an MTV-ready hit. A parking garage battle is egged on by bouncing cars flashing their high beams. The climactic showdown between Lambert and a Def Leppard-quoting Clancy Brown takes place amid an enormous neon sign just for the pyrotechnic opportunities it presents.

Mulcahy never got his due as a cinematic stylist. He left the production of "Rambo III" when it became clear the powers that be didn't want his hyperactive stamp on it. "Razorback," his "Jaws"-with-a-pig debut, and "Ricochet" rival it for panache, but "Highlander" remains his gonzo masterwork. Like Freddie Mercury sings over the end credits, it's a kind of magic.

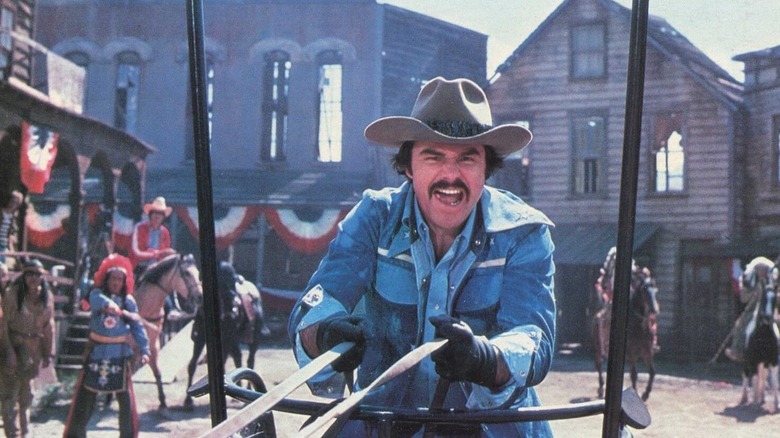

Hooper

"Smokey and the Bandit" is the smoother Burt Reynolds-Hal Needham collaboration. Cases could be made for "White Lightning" and "Sharky's Machine" as the better Burt actioners. But "Hooper" is the only Burt Reynolds movie about Burt Reynolds and his dying-breed relationship with the genre, and it happens to be a riot from one crushed fender to the other.

Stuntman and all-around wiseacre Reynolds is 42 years old, which is ancient in stuntman years. The only way he can make it through each crash, fall, and barroom brawl is with painkillers and Coors. The studio wants bigger and bigger stunts for less and less money. It's not lost on Reynolds that he's just a professional crash dummy for the real money-makers, like Adam West's pseudo-007. And yet, even with news that one more mistake could leave him paralyzed, he can't help himself. It's a compulsion only other stuntmen understand, like director Needham and the many others who, in a marked change, play themselves on screen.

Needham, the first stunt performer to win an Oscar for their work, and Reynolds, famous for doing more of his own than he probably should've, pushed the audience out onto a high-wire they knew only too well, teetering between raucous fun and creeping mortality. The next trick always has to be bigger than the last, but there's also a chance that the next trick is the last trick. After the fear and before the glory, if they're lucky, comes the sigh — or, in the case of "Hooper," the blooper reel.

Hot Fuzz

When movie-addled small-town police officer Nick Frost decides to educate supercop Simon Pegg on the finer points of buddy cop cinema, he selects two DVDs without even looking. "'Point Break' or 'Bad Boys II'?" It's a testament to director Edgar Wright and co-writer Pegg that not only did they call a shot that bold, but that their work now appears alongside their admitted influences on lists like these. "Hot Fuzz" isn't just a love letter to the genre. It's also a syllabus.

Lesson one of many: Buddy cop action is infectious. When Pegg gets transferred to a town so small that its most famous resident manages the grocery store, there's not much crime for a serious crimefighter like him to stop. But the more Frost reads from the gospels of Riggs and Murtaugh, the more disproportionately dangerous their patrol gets. Before long, they're taking on quick-drawing priests in the town square, reloading service shotguns in the frozen foods section, and impaling the big bad in a conspicuously elaborate set that seems tailor-made for destruction. Admittedly, one of those things happens by accident, but that's just fate bending to the will of buddy copdom. Wright's laser-guided camera has never had a better reason to show off; through his lens, as hilarious as they are, Pegg and Frost are nothing short of bona fide badasses. This is the rare parody that has its cake and blows it up, too.

The Human Tornado

Cornered in bed with the wife of a racist sheriff by her husband, the legendary crimefighter-pimp-comedian Dolemite sees no way out but nude. Jumpsuit in hand, he dashes to the veranda and takes a running dive off the side of a perilously steep hill. Just before he touches ivy, Dolemite freezes. "So y'all don't believe I jumped, huh?" he challenges in voice-over as his bare form rewinds to the ground. "So watch this good s***!"

With this instant replay, producer-star Rudy Ray Moore threw down the gauntlet. Audiences who thought that "Dolemite," the cinematic debut of Moore's stand-up alter ego, was outrageous had another thing coming — and if they missed that thing, he'd happily show them again. This is the work of an emboldened artist. Moore let his profane, perverse, and distinctly principled imagination run as wild as it ever had, at least until he made a movie about being the devil's son-in-law. Instead of saving his act for later, "The Human Tornado" opens with a tight five. Instead of a mostly off-camera seduction, "The Human Tornado" finds room for several increasingly loony sex scenes, the last of which sees Dolemite caving-in the bedroom with sheer pleasure. And then there's the bigger, badder kung fu.

When striking Bruce Lee poses, Dolemite makes the same noise cartoon characters do when shaking their head sober. Jumping kicks, no mean feat at normal speed, are triple-timed into absurdity. Any chop cool enough to show once is cool enough to show two, if not three, times. There's a moment of uncertainty at the very end when it appears that Dolemite may be immortal. The magic of "The Human Tornado" is that none of this exactly plays as a surprise.

Inception

The legacy of "Inception" is a spinning top. If it stays that way, dream-thief Leonardo DiCaprio is still in the land of nod. If it falls, he's back in cold, hard reality. The suspense of that infuriatingly simple image was enough to overshadow the fact that "Inception" is nothing but spinning tops, any of which would bring the entire concept crashing down if they so much as slowed. This is the skill of Christopher Nolan, a clockwork tinkerer handed the keys to Big Ben.

From a distance, "Inception" makes your eyes cross. The rules of entering dreams to steal trade secrets. The riskier rules of entering dreams to influence behavior. The telescoping of dreams. And then there's the vocabulary: totems, kicks, limbo. But Nolan only shows the audience one spinning top at a time, a simple movement in a complex pattern. A real-world car crash rattles the dreams of passenger Joseph Gordon-Levitt. To demonstrate, Nolan dusts off an old Fred Astaire trick and turns a rotating hallway set into one of the most electrifying action sequences of the millennium. Sure, diagrams scrawled on napkins and talk about shared subconsciousness get the job done, but not as well as showing dream architect Elliot Page fold Paris hamburger-style. If any of it stops making sense, just watch the spinning top. Nolan will always mesmerize you, if you let him.

Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom

"Raiders of the Lost Ark" is one of the greatest adventure films ever made. No chase, fight, or explosion in it is anything less than iconic. "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" manages to sneak in a set piece involving every form of transportation available in 1938. What edges out the action in "Temple of Doom" over those, let alone the rest of Steven Spielberg's filmography, is obvious.

During production, producer George Lucas was going through a divorce. Spielberg was reeling from a breakup. Harrison Ford suffered a spinal injury in the middle of production, taking himself out of commission for over a month, leaving only stuntman Vic Armstrong's back to pick up the slack.

"Temple of Doom" is Spielberg and Lucas hitting the speed bag in their soundstage-sized garage, getting all their anger out. It opens with a location-defying Busby Berkeley dance number just because they wanted to shoot one. Indy enters in a "Goldfinger" tuxedo, a symbol of Spielberg's lingering frustration at never getting to play with the world's greatest spy, and stumbles through more hells in under two hours than James Bond managed in the surrounding decade. Rafts triple as parachutes and sleds, rope bridges as ladders and swing sets. The climactic mine cart chase is one of the most impressive mixes of full-scale sets and stop-motion miniatures ever attempted, let alone seamlessly executed.

That hell-for-leather charge doesn't serve all of the material well — the gross-out dinner scene has only gotten grosser —but the first 20 minutes and last 40 of the film are as breathlessly astounding as action-adventure gets, now and forever.

Ip Man

As the titular legend and Wing Chun grandmaster, Donnie Yen is the image of calm. He shows neither joy nor pain in battle, not even during private exhibition bouts. When one opponent draws a sword, he counters with a feather duster as if it's just as deadly. For a while, the closest Ip Man gets to rage is when a fight costs him his favorite vase. Then the Japanese invade and kill his best friend over a bag of rice.

It's a standing invitation from Japanese general Hiroyuki Ikeuchi: Win a fight with one of his karate-trained soldiers, win a bag. "I want to fight ten people!" screams Yen, not so much waiting for an answer as for the victims. In this dojo, drained of all color but the red of blood and the rising sun, Yen is a grim reaper among ghosts. They take defensive stances. He doesn't. He knows what's coming. The first attacker learns the hard way, yanked out of a flying kick and curb-stomped into the mat. The rest don't receive so much mercy. His punches blur over skulls, sternums, and noses, too fast for the camera's shutter to separate the strikes.

Donnie Yen was already a lauded martial artist by the time "Ip Man" came along, but Sammo Hung's brutal choreography and Wilson Yip's coiled direction unleashed something in him. In his hands, that feather duster is just as deadly as a sword.

The Italian Job

Michael Caine exits prison with a Cheshire Cat grin and a, "Cheerio, lads!" His name here is irrelevant. Though he'd already been fine-tuning his devil-may-care act for years, most winningly in "Alfie" and the Harry Palmer trilogy, "The Italian Job" would be Caine's movie-star baptism.

And just as Caine was built to play a gentle-lad thief, the kind who never loses without a smile on his face and three different back-up plans on the tip of his tongue, the Mini Cooper was built to play his noble steed. The manufacturer did the production no favors, selling them six in Union Jack colors at list price. By that accounting, it has to be one of the most profitable advertising campaigns ever launched. BMW could run ads today made of nothing but automotive acrobatics from the film's climactic heist and see a bump in its valuation.

The getting-away-with-it glee of the sequence is more or less autobiographical - producer Michael Deeley scouted Turin specifically because the city wouldn't know what hit them. Free of any expectations for a major film shoot, the crew got away with four-wheeled murder. Down cathedral steps. Up conveniently sloped arenas. Through museums. Around rooftop racetracks and eventually over rooftops. The stunt drivers turn their cars into acrobats tumbling around the world's most stunning big top. And that's what makes "The Italian Job" a stone-cold classic of British cinema on and off the streets: It's incredible entertainment with the greatest of ease.

Jackass 3D

"I'm Johnny Knoxville and this is 'The Jet Ski'," says the ringleader of the Jackass circus. His only protective gear is a baby-blue tuxedo — part of the bit — and an American flag helmet, a tribute to daredevil king Evel Knievel. What sets Knoxville and his merry men apart from that legend, however, is on the other side of the pool, ramp, and hedges.

There's nothing there but dirt and glory. These are not stuntmen. They are folk heroes, self-appointed by accident, putting their bodies on the line doing what nobody really asked them to do. Bless them for their hilarious sacrifice.