The Myanmar concept of hpone refers to this innate, mystical power that men supposedly possess, and that is believed to be sapped if, among other examples, men’s clothes come in contact with women’s. Hpone is applicable not just in laundry but across all aspects of our culture, including, for instance, religion. It’s believed that only a (cisgender) man can become the next Buddha because only men have hpone; as a result, only men can touch the Buddha statues at the pagodas, and there are certain areas at most pagodas that women are forbidden from entering.

While a woman could never possess as much hpone as a man, she can rob the latter of his, or at least reduce his hpone by, for instance, making a man sleep on the floor while she sleeps on a bed or sofa or inhabits any space that is physically (and thus metaphorically) higher than his. I imagine this is what it must be like when you live with, say, the pope, except imagine how exhausting it is to have to treat every single man that you know with the same reverence as you do the pope.

Hpone is also the reason why a lot of Myanmar households never wash men’s and women’s clothing together, nor hang them up to dry on the same rack. In the hallway outside my parents’ bedroom are four tall plastic baskets, two positioned on each side of the door. I was taught early on that one pair of baskets was for my mom’s clothes, and the other for my dad’s; the same was true for my brother’s clothing in respect to mine and my sister’s. Our clothes could never be washed in the same wash because that would negatively impact my father’s or my brother’s hpone.

Because women’s clothing, particularly underwear and garments worn on the lower part of the body (such as skirts, trousers, or hta meins), are unclean, they especially could rob a man of his hpone if they came in contact with said man’s clothes; if my mother’s hta mein were washed in the same wash as my dad’s pa soe, my dad’s hpone would be hurt as a result. If we played in the backyard where the laundry was hung up to dry, A May would keep a close eye on my brother to make sure he didn’t run under any of the poles that had the women’s clothing on them, lest our underwear graze the top of his head.

Imagine how exhausting it is to have to treat every single man that you know with the same reverence as you do the pope.From an objective standpoint, the concept of hpone and its many rules sound sexist and baseless (and they are), but the fear of diminishing a man’s hpone is one that almost all Myanmar people hold. In 2015, a woman was arrested after she shared a cartoon of then–newly appointed state counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and military commander in chief Min Aung Hlaing on Facebook and commented that if the commander in chief loved the state counselor so much, he should wear her hta mein as a bandana around his head. Min Aung Hlaing was outraged that a woman dared even make a joke that would imply a lessening of his hpone and took her to court, and the defendant was found guilty under an antidefamation law that landed her a six-month prison sentence.

As the oldest child, I was always told that I needed to get along with my brother and sister because I would be left in charge of them if something were to happen to my parents. And yet, even though I was at the top of the hierarchy, I was also taught from a young age that my little brother was inherently and spiritually better. Whenever I questioned these rules, my mom would shut me down and reply, “Well, whether you like it or not, we are Myanmar.” She was right. It was—is—ingrained into our culture that men are innately superior to women, and while I suspect many women know that it’s wrong, it’s difficult to undo a lifetime of social conditioning.

In 2019, a male Myanmar artist held an exhibition in which he challenged this belief that men’s and women’s laundry couldn’t be washed together. But while it seemed that several older women knew it was sexist and outdated, they still couldn’t teach themselves to unlearn a decades-old practice. One viewer admitted, “Even now, I continue to follow the custom; however, I will teach my own children that it is wrong.”

If just a piece of women’s underwear has the ability to take away this inherent, almost godlike essence with which men are naturally born, who holds the real power here?In our family specifically, it was even more crucial to separate our laundry because, as in most military families, my mom followed the widely held belief that it would be bad luck for a soldier if he, or his clothes, were somehow soiled by coming in contact with women’s clothing. My dad joined the army long before I was born, so growing up, he was often posted to different parts of the country. He did, however, come home every few months, and in that time, my mother wasn’t going to risk leaving her children fatherless by not separating their clothing just because she was too lazy, or because she wanted to make a statement in the name of feminism.

When my dad was away, Mom and A May kept things running. My mother worked to pay for everything while A May did the housework. It is fitting that I call my grandma A May because I did—do—essentially have two mothers. Mom worked five days a week, attended all the parent-teacher conferences, and she was always on top of Tooth Fairy and Santa duty. A May taught us how to read and write as well as basic math, did all the grocery shopping, and cooked all our meals. Every morning, Mom would make the rounds through our three bedrooms and wake up each one of us, getting our backpacks ready while we crawled out of bed, and A May would fry rice and bacon in the kitchen.

By the time we were showered and dressed and came downstairs, Mom would plate our breakfast while A May packed our lunches. If something needed to be fixed around the house, they busted out the toolbox and mended it themselves. I had a lot more admiration and respect for A May and my mother than I did my father or my grandfather, and so it confounded me that they assumed that they were nonetheless spiritually inferior to these men, neither of whom were around to help them feed, teach, and raise three young children.

At the peak of my teen feminist angst, I became a strong advocate of the pro-period movement. As a girl who got her first period embarrassingly early in life, I also learned very early that if women’s underwear was like a chunk of kryptonite to a man’s hpone, period-stained underwear was the literal bleeding core of a kryptonite volcano. As a teenager, Mom would make me put my used pads into opaque black plastic bags and, like a fast-moving ninja, swiftly toss out the bags before my dad next went into the bathroom so as to spare him the horror and embarrassment of coming face-to-face with a bag that contained a woman’s used menstruation products.

Imagine that: choosing to stop and hinder your own ability to do your job simply because you are terrified of walking underneath a woman’s skirt.Sticking to my role of the rebellious teenage feminist, I purchased several pairs of period underwear, which, as the name suggests, is underwear that you wear during your period to soak up your menstrual blood. When washing your period underwear, you first put it under running water and wring out all the blood until the water runs clear, and then you can pop it in with the rest of your laundry. The first time I put my period underwear in the same wash as Toothpick’s clothes, I half expected A May to burst through my front door after having sprinted from Yangon to Oxford in a matter of minutes, screaming at the top of her lungs, “Did you learn nothing from me? We are Myanmar! We don’t do this!”

But of course she didn’t, nor did she know, and I just stood there, equally proud of the stigmas I had overcome and ashamed of how I had turned my back on my culture, watching his and my clothing go round and round in my washing machine, my dirty period underwear mixing and getting tangled up with his spiritually superior shirts and defiling his hpone.

To protest the 2021 military coup d’état, women activists launched what became dubbed the Hta Mein Revolution. In order to deter, or at least slow down, police and military personnel from marching through the streets to break up protests, protestors hung up clotheslines of hta meins and underwear. Because the Myanmar male ego’s belief of hpone truly is a curse that was tactfully used against them, in this case, the idea was that the soldiers and police would feel compelled to remove these clotheslines before marching onward (which they did). Imagine that: choosing to stop and hinder your own ability to do your job simply because you are terrified of walking underneath a woman’s skirt. In Myanmar, hta mein is spelled which also means “we rise”—sometimes life and language are just perfect in their natural poetry.

Because it’s funny, isn’t it—if just a piece of women’s underwear has the ability to take away this inherent, almost godlike essence with which men are naturally born, who holds the real power here?

___________________________________

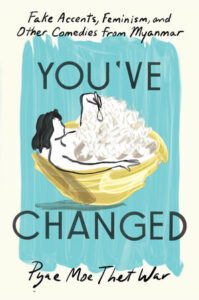

Excerpted from You’ve Changed: Fake Accents, Feminism and Other Comedies from Myanmar by Pyae Moe Thet War. Copyright © 2022. Available from Catapult.